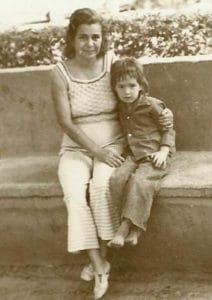

My mother and me. Bell Gardens, CA 1973

This is the second installment in a series: “Understanding Poverty from the Inside.”

It was first posted in The Huffington Post in 2017.

When I think of poverty, images from my own life flood my mind before a word even comes through. Even today as I write, I struggle to commit the words to print. I am trying to distinguish whether it is the smothering shame I had for being poor or the invisibility, pain, and insecurity of being poor that suspends the stroke of the keyboard.

Internal Struggles

The truth is that I could not have written this when my mother was alive. “Cover up, like Nixon” was the maxim; although I didn’t know what she meant until I was an adult.

Shame is passed along like a simple game of tag, “Tag, you’re it.” As a child, I did not understand why we had to hide the brand new toaster when the social worker came or pretend not to be home when the landlord knocked. It soon became clear; we weren’t supposed to have anything new or anything nice.

Window Shopping

For the majority of my adult life I felt like I was window-shopping at the grocery store, bookstore, and even coffeehouse. The difference between what I wanted and what I needed, played back and forth in my head like a tennis volley. Wants felt self-indulgent and decadent. “Should I pay an extra dollar fifty for them to whip milk into my coffee? Nah, I will just have a house coffee, thanks.”

I was recently reminded of my past as I watched the documentary City of Gold. The movie transports us in and out of ethnic mom and pop restaurants, driving past abandoned buildings, graffiti, concrete, grassless lawns; as my seatmate stated, “Los Angeles is ugly.” I whispered back, “These are the poor areas of Los Angeles.”

I did not do anything to contribute to my poverty, it was mere circumstance. I was born into it, like you were into your family. But it is a hidden, unspoken barrier that separates you and me. I want to break this barrier today and show you who I am. I want to bring humanity and compassion to the issue of poverty.

Let me explain:

As tears drip from my face at this moment, I believe that it is more than shame; it is the pain of being poor and the experiences that haunt me. Among other feelings, being poor meant not having a choice. Protest was not an option, I—we—had no choice about what I ate, where I lived, and the clothes I wore.

Choice?

I can’t pinpoint the moment I first felt it, but the feeling was deeply embedded in my psyche. The fear of being exposed like a slow leak of poisonous gas followed me around. The terror of exposure was once crippling, but today I am reminded that this is not just my story; today, in the United States, 14.5% of the population experiences poverty; 22% of Californians experience poverty. I was not alone in this and am not speaking about something that has been eradicated. Poverty continues to cripple communities.

Remnants

I want to walk you through the smells, the textures . . . all of it. I will take you through one of my homes—one of over 14 different apartments I lived in during my childhood, but all of the elements are the same. Each move guaranteed a few days and nights without electricity, the windows covered by towels or sheets until the furniture a remnant from the Salvation Army Thrift Store, the tiny kitchen stuffed with plastic plates, Alpha Beta dish sets, juice glasses from the Doña Maria Mole jar, AM/PM 32 oz. graphic cups, pots and pans made of aluminum sold at the 99 cent store, generic soaps, shampoos, cleaning supplies with faux sponges to clean. The bathroom towels followed us from apartment to apart each worn and dingy, the decorative washcloth embroidered with a swan served as the solo accent decor of the bathroom.

Earthquakes and Government Subsidies

The dining room table with matching chairs arrived as the result of the 1987 earthquake. Our tragedy came with perks. We lost our apartment, which was condemned from the damage, and everything in it. We got government vouchers to an East Los Angeles furniture store where, for first time, I got a bedroom set (bedframe with detached headboard, two side tables, and a dresser). Each drawer made of a thin sheet of particleboard . . . gold knobs and laminate. I was careful not to pull too hard or the plastic wheels would show their fragility.

I was 18 when I received my first sheet set that matched: one fitted sheet, one flat sheet and two standard pillows. Our furniture finally matched: a couch, a coffee table and a bureau. Each piece carefully placed in what came to feel like a nice shoebox, with walls, the doors hollow and light. The furniture matched the construction of the apartment simple, quick, and ready. Laminate glue holding together a illusion. My definition and experience of being poor: a top, visible sheet over a multilayered experience that takes you deeper in.

Who is poor?

Part of this study was simply to ask the women how they defined being poor. As one of the criteria for the study, they already matched the measure for poor as defined by the U.S. Government. Each woman—as did I—qualified for free or reduced-cost lunch and self-identified a having been poor

I began this project by thinking about the definition of poverty as someone who has experienced poverty and what exactly the standard definition overlooks. To arrive at a more nuanced and subjective understanding, I asked participants how they would define poverty. (For a mini biography of the study participants, see the first installment in this series, here.)

Below are the responses they provided:

Luna stated:

Let’s see. I would define it . . . for me poverty is not being able to afford somewhere to live, having food in your refrigerator, or clothes. Not having enough money to make a living and being in a place that is just really difficult financially.

Violeta said:

I think if I were to put it in two words, “not having.” So, not having money, first and foremost, but also not having sometimes-basic needs for school. Sometimes not having the proper school supplies, not having . . . when I was in athletics, not having the proper shoes or the proper athletics gear and how to raise money to get those things that I needed. Not having access to tutors when I was doing badly in math. Not having sometimes my parents around, especially my dad because he had to work different jobs to basically make ends meet. I think those two words, “not having” is like for me what poverty really means. It’s like a lack of, not having. [emphasis mine]

Carmen stated:

I define poverty, being unable to do things that force you to have to make ends meet where the children are an intricate part of that involvement, where they become, in essence, part of the child labor in the family economy. So I think that when a family really struggles financially, they have to sort of pull from any avenue is when you see yourself in a situation where you’re poor. [emphasis mine]

Monica offered:

I guess people that have a low basic unsteady income and struggle paying the basic needs, like basic groceries, utilities, housing, struggle to pay for it. The basic roof over the head, meals, you know.

Patricia explained:

Well we do free and reduced lunch, plus additional factors like receiving – but we do recognize the qualitative niches of like, okay, there’s times when families are unstable and stuff, so there was an early period in my family’s life when we were really unstable, like my dad would like have $20.00 for food and he’d be like, should I go gamble or not?

Susana offered:

For me, I guess, when I think of poverty, I think people who can’t afford food or economical hardship, so it’s all kind of economical, in terms of just money, not having enough of it, or not having enough to survive. So that’s how I think about poverty. So I guess it would be, “Poverty is the level of having either money or not sufficient money to survive.” So when, I guess, in an application, compared to the medium household income, we always fell below that, so that’s why I put “Yeah.” And I guess in that category, I do fall under free and reduced lunch, so it’s poverty. Okay, because that’s gonna be kinda hard to gauge poverty, because in my eyes, I don’t see myself or our family as poor, but then in comparison to certain things, like if we got the free and reduced lunch, then we were. So if we do the free and reduced lunch, all of the years. I always got it.

Consuelo offered the following definition:

So to me, poverty is just not having anything, like nothing to eat, really, really struggling. To me, poverty means that you have nothing. You have nothing to eat, no clothes, you’re practically almost homeless. And I feel like sometimes, I don’t feel that I was ever hungry or didn’t have anything on the table. I mean, I didn’t have the best of stuff or food, but I had stuff to eat. So to me, poverty is just not having anything, like nothing to eat, really, really struggling.

Maria stated:

I think its lack of resources, like difficulty surviving every day. Like having to worry about having money to eat, to pay for what you need.

Vanessa explained:

I think my definition, I guess, based on my experience, would generally be poverty includes you not having money to even eat, to purchase any lunch, like school lunches or even at the grocery store or for dinner or what have you, so that feeling of going without, being hungry, to me, it would define poverty. But also having to figure out how to take care of medical care, having parents with medical needs and not having even insurance, I would include that. And as well as having a home, so being homeless, I think is, for me, that defines my experience of being poor or experiencing poverty. So I think those were the main factors. So I think poverty would also be like, should consider or include the fact that if you depend on credit, then it doesn’t make you rich, it just makes you that you’re – And I don’t think we usually consider that, or people who might be in between that might be like, okay, we have X amount, we make this much money, they assume that you can afford all these extra things, but it’s like well, if you have all these bills to pay . . .

Shalah stated:

I know there are different layers of poverty, but how I would define it right now, at 34 years old and in all my experience, is not having clean clothing, shelter, not feeling supported, feeling alone, and seeing a lot of those men in downtown L.A., that’s the picture I paint when I think of poverty . . . so when I think of poverty and defining it, I think of Los Angeles street and all those people out there, that’s what I think of. I think of not having a home. [emphasis mine]

Defining Poverty

Many of the participants’ definitions made reference to a lack of financial security. Six of the participants gave definitions that separated and objectified poverty; they did not make references to themselves or their own lived experiences. As such, their responses were consistent with standard definitions of poverty. Patricia, Consuelo, Vanessa, and Susana made reference to their family or their experience.

In retrospect, I realized that the question itself was loaded. I wondered why they had offered up standard definitions—why not say, “I have tried to forget that painful past, poverty is horrendous.” (Or, were they, in fact, “forgetting” by virtue of offering such conventional definitions? Did the question provoke memories of a forgotten time, a repressed time?) Was the fact that I was their peer/colleague influencing their answers? Were their lives as doctoral students that far removed from their experiences of being poor? Perhaps they had intellectualized their own experiences. Undoubtedly, it is easier to address an issue when you have some distance from it. Could it be that these women had been socialized (and educated) to discuss social issues in a rote and objectifying way. Perhaps these responses had not been thought out. Perhaps these women had been caught off guard.

I thus realized that the difficulty in answering the question, “How would you define poverty?” It may have to do with the question itself as well as with the timing of the question. I could have provided a prompt to get what I wanted by asking for a definition that included a personal experience. Such a question could have looked like this, “Considering that you experienced poverty for the majority of your life, how would you convey what it means to be poor to someone who doesn’t understand the layers of deprivation, doing without, and sacrifice?” However, this would have compromised my study, I wanted the interviews to be organic and fluid.

Vanessa’s definition touched on many aspects of poverty, including having bills to pay, being homeless, and lacking medical care and insurance. Violeta remarked on how poverty had affected her participation in school sports, academics, and family time. Both of these women shared a part of their own history in their definition without explicitly stating that their descriptions referenced their experience. Shalah acknowledged the multiple dimensions of poverty, including “feeling alone,” then shifted her definition to “the men in downtown L.A.” Consuelo and Susana used their definition to exclude themselves from having been poor.

Although bound by certain constraints due of the dissertation format, I tried to represent their stories, uninterrupted by my own questions and curiosities. Instead of probing and directing the discussion, this testimonio format honors participant voices and interpretations without judgment about accuracy. The stories themselves and the way they are told is the story—interruptions, self-corrections, variations, self-interpretations, and all. Telling one’s own story and honoring one’s own voice democratizes the experience. Giving voice may not bridge the divide between gender, race, and class, but it validates one’s story as equal in importance to the majoritarian story—the privileged discourse that has historically supplanted the discourse of the “other,” in the case of these women, the poor and people of color. Narratives are about choice, and each of these women shared what they felt they could share. My next installment gives a first-hand account of the personal challenges the women in this study confronted by being poor in regard to their housing and their neighborhood.

The next installment in the series is: Understanding Poverty from the Inside: Home and Neighborhood.

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave